Masculinity on for Show

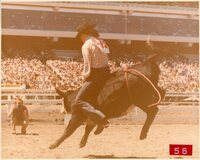

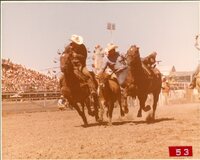

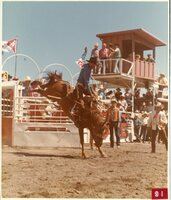

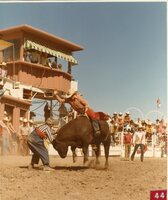

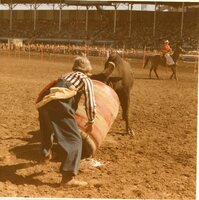

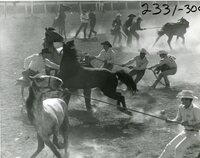

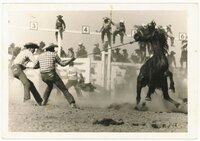

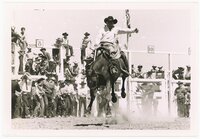

A central spectacle in the marketing of the Calgary Stampede is the danger inherent in its rodeo events. Competitions such as bull riding, saddle bronc and bareback riding, steer wrestling, team roping, tie-down roping, breakaway roping, and barrel racing are all sold on the thrilling promise of witnessing the “last of the cowboys” perform daring, one-of-a-kind feats. Each event dramatizes a struggle between human and animal, where life and death hang in the balance, often literally on the back of a horse or bull. The thrill of this danger both real and carefully curated, forms a cornerstone of the Stampede’s enduring appeal.

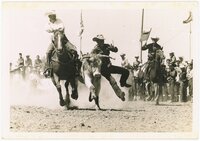

Early programming guides for the Stampede referred to cowboys as “knights of the range,” a revealing metaphor that aligns the cowboy with the medieval knight: a figure of masculine virtue, courage, and moral authority. This comparison situates the cowboy not merely as a worker or athlete but as a mythic hero of the modern frontier. By invoking the language of chivalry, the Stampede framed the cowboy as the embodiment of a new Western code of honour—bravery, toughness, and stoic endurance—transposed from the battlefields of medieval Europe to the open plains of Alberta.

The marketing materials of the early Stampede leaned heavily on this imagery, pairing romanticized language with sensational taglines that invited spectators to “see the danger and excitement” of rodeo life. Posters and programs often featured dynamic images of cowboys being thrown from broncos or tumbling through the air mid-fall, dramatizing both the peril and the spectacle of the sport. There was, and still is, no denying the danger of rodeo. An early article describing the rodeo cowboy paints the stakes vividly:

“He can be killed in an instant or crippled for life, by a kicking hoof or a driving horn. He’s seen it happen to his friends—perhaps two of them a year. He’ll suffer a bad break, a leg, a rib or maybe his neck an average of once every four years, but he’ll be back to pay his entry and ride again long before the doctors agree the break is healed.”

This passage underscores how risk itself becomes central to the cowboy’s identity. The willingness to face injury or even death, in pursuit of honour and spectacle transforms rodeo into a ritualized performance of masculinity. To ride despite danger, to endure pain without hesitation, is to enact an idealized version of manhood rooted in courage and physical mastery.

For most spectators, this performance offers a vicarious thrill rather than a lived reality. Few in the audience would willingly risk their lives in such a way, but by watching, they participate in a collective fantasy of frontier heroism. The rodeo ring becomes a stage where masculinity is not only displayed but reaffirmed through risk, resilience, and spectacle.

In this context, the cowboy becomes more than just a performer or stuntman; he stands as the symbolic embodiment of an imagined “Old West” masculinity. The spectacle evokes nostalgia for a bygone era when men were perceived as rugged, self-reliant, and defined by physical courage and endurance. The rodeo, therefore, functions not simply as entertainment but as a form of cultural storytelling, one that continually reinscribes ideas of masculinity, risk, and authenticity. This idealization of a “better time” serves both as a marketing tool and a cultural myth, allowing the Stampede to celebrate a romanticized version of the past while reinforcing traditional gender ideals, even as modern life moves steadily away from them.