The Cowboy in Arts and Culture

As the Calgary Stampede grew larger and increasingly popular with each passing year, it began to spill beyond the rodeo grounds and into broader arts and culture. By the 1960s, this cultural presence was amplified by a surge in cowboy-themed media that dominated television screens and popular entertainment. Westerns became a staple of North American home life—shows like Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and Rawhide brought the mythic cowboy directly into living rooms, reinforcing the romantic image of the rugged, self-reliant man facing the untamed frontier. This media landscape helped solidify the cowboy as not just a regional or historical figure, but as a cultural archetype—an enduring symbol of courage, independence, and traditional masculinity.

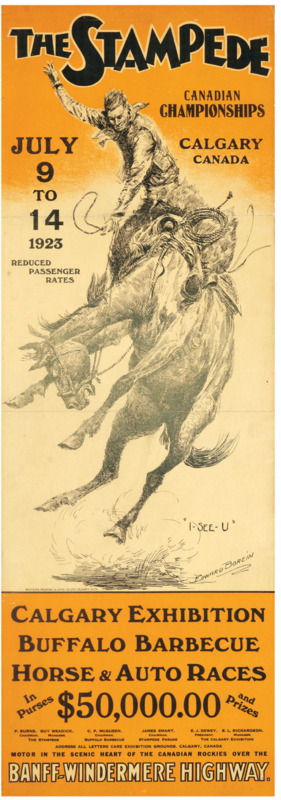

Within this landscape, the Calgary Stampede both contributed to and benefited from this larger Western revival. Its imagery, promotional materials, and annual celebrations intertwined with broader trends in popular culture, from film and television to visual art, music, and fashion. The Stampede’s parades, posters, and exhibitions became part of a feedback loop of cultural production: they drew upon the familiar tropes of Western heroism, while simultaneously feeding them back into the cultural imagination.

This reciprocal relationship between the Stampede and popular media helped to sustain and modernize the mythology of the cowboy. Art and entertainment did not merely reflect the Stampede, they amplified its ideals, aesthetic, and emotional power. Whether through rodeo posters painted in bold, cinematic style or through the presence of real cowboys appearing at film festivals and parades, the Stampede extended the life of the frontier myth well into the modern age. It became a living, recurring celebration of the imagined “Old West,” one that continued to romanticize its masculine ideals and keep the folklore of the cowboy alive for new generations.

Below is a collection of some highlights of Stampede intersection of arts, culture, media.

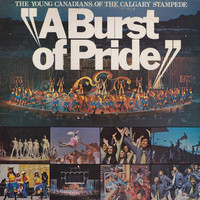

Stampede and music have always gone hand in hand. Not only did the Calgary Stampede establish its own showband, famous for its dynamic performances both on the grounds and around the world but it also created opportunities for emerging performers. One of the most notable examples is The Young Canadians, a performance troupe that gives talented youth from across the country the chance to develop their skills and appear in the Stampede’s iconic Grandstand Show.

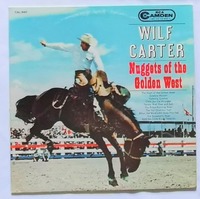

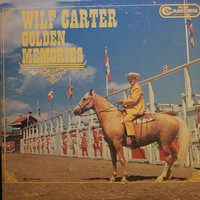

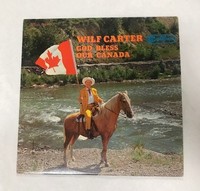

But the greatest champion of Stampede music and western myth-making was Wilf Carter. Born in Port Hilford, Nova Scotia, Carter moved to Calgary, Alberta, in 1923 at the age of nineteen. He quickly embraced cowboy culture and became a regular musical presence at the Calgary Stampede, where his singing and storytelling helped shape the event’s musical identity. His 1960 album Songs of the Calgary Stampede stands as a tribute to both the festival and the frontier spirit it celebrates.

Carter’s music, along with groups like The Young Canadians—reinforced and expanded the Stampede’s image of grandeur, community, and western heritage. Together, these performers helped promote the idea that romanticizing the frontier and celebrating western culture is not only meaningful but something that can be expressed across all forms of art. Their contributions enriched the Stampede’s mythology and ensured that its traditions continue to resonate with new generations.

The visual arts also play a major role in the story of the Calgary Stampede. The most famous artistic expression associated with the event is undoubtedly the annual Calgary Stampede poster. Always charged with raw emotion and steeped in the romanticized imagery of the West, these posters have become iconic symbols of Stampede culture. They help define the event’s visual identity, not just on the Stampede grounds but throughout the city and beyond. Even people who have never attended the event can instantly recognize Stampede imagery because the posters have cemented a specific visual motif in the public imagination.

Yet there is another visual art form within the Calgary Stampede that deserves equal attention for its cultural importance: the bronze statue, especially in its role as the rodeo trophy. These trophies represent the pinnacle of the Stampede’s artistic celebration of rodeo culture. The most distinguished rodeo awards reflect the grandeur of the event itself and embody the celebration of Western masculinity that the rodeo has long promoted. Typically, these bronze sculptures depict a cowboy atop a bucking horse—caught mid-action, on the edge of being thrown yet still in command. This frozen moment of tension and triumph captures the essence of rodeo heroism.

As discussed earlier, the rodeo events themselves romanticize and reinforce traditional ideals of Western masculinity—the notion of a bygone era “when men were truly men.” The rodeo trophy extends this narrative, casting that ideal in metal so that it can be displayed, admired, and preserved indefinitely. In bronzing the image of the cowboy at the height of his struggle and control, the trophy enshrines the mythic peak of Western masculinity, making it both a personal award and a cultural monument.

Below we see some rodeo champion holdig there bronze prizes:

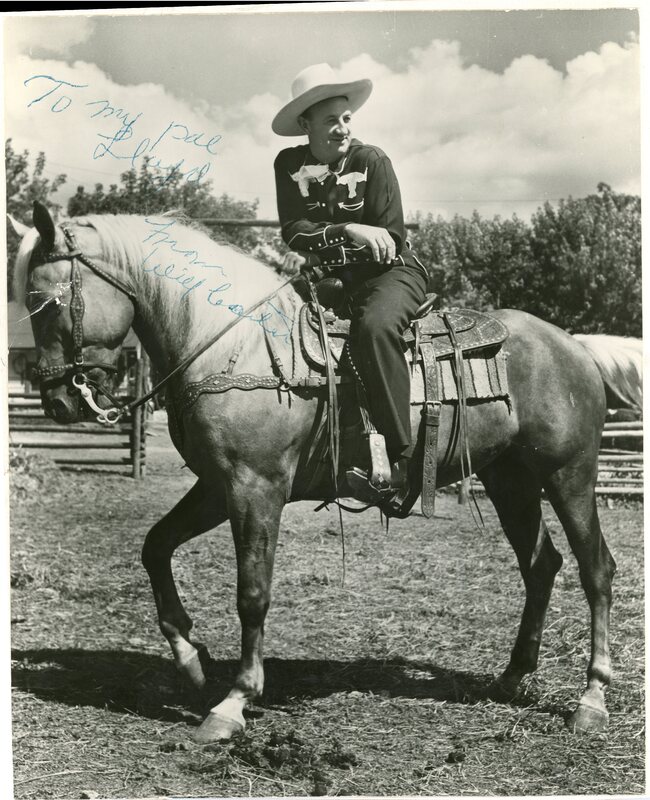

The Calgary Stampede has long been intertwined with popular culture, particularly the pop-cultural fascination with the West. Throughout the mid-20th century, many well-known television cowboys visited the Stampede as celebrity guests. The autograph shown at the top, for example, is from Leo Carrillo—the actor who portrayed Pancho, the loyal sidekick to the Cisco Kid in the popular 1950s western television series. This tradition continues today: in 2022, Kevin Costner, widely known for his role as a modern cowboy in the hit series Yellowstone, made an appearance at the Stampede.

Celebrities have always played a significant role in shaping the Stampede’s public image. They have served as Grand Marshals of the parade, performed live music, appeared in full western gear, and happily signed headshots for fans. Over time, these figures became part of the Stampede’s brand, reinforcing the event’s association with Hollywood-style western glamour.

The Stampede also produced its own form of celebrity—the champion cowboy. Contestants who gained fame by winning big in Calgary often found their names, faces, and reputations used in advertisements. Their ruggedness and authenticity were leveraged to sell products ranging from cigarettes to beer, all marketed through the desirable image of western masculinity. The Calgary Stampede cowboy became a cultural symbol, one that could attract crowds and help companies project a sense of toughness, independence, and frontier spirit.

This comic strip style ad below is for Camel cigarettes featuring 1949 stampede champion Eddy Akridge.

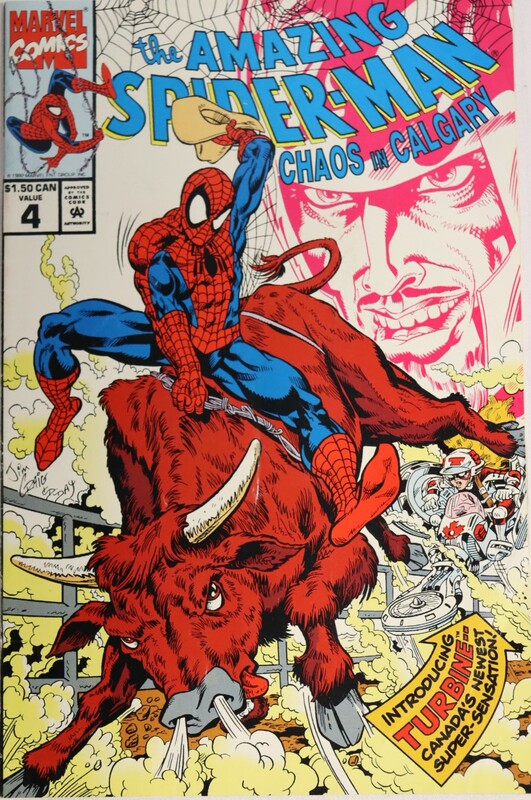

Beyond real-world celebrity, the Stampede even found a place in the realm of fictional pop culture. A 1992 issue of The Amazing Spider-Man featured the superhero visiting the Stampede, fighting crime—and, most memorably, riding a bucking bull on the cover. Although the comic was sponsored by Petro-Canada as a marketing tool, it also demonstrates the cultural power and national visibility the Stampede had achieved. The event later appeared in X-Men comics and even Archie, each time emphasizing the excitement, danger, and western energy associated with Calgary’s biggest annual celebration.

The Stampede also created its own homegrown pop-culture figures, often aimed at making the event more appealing to children. One such figure was Beverly Kendall, a small child in the 1930s who was dressed in western attire and promoted as a kind of miniature mascot, a tiny cowboy who symbolized the future peak of western masculinity. Another was the non-human mascot Harry the Horse. Though hardly a model of rugged masculinity, Harry, often depicted wearing western clothing, played an important role in teaching children the romanticized ideals of the frontier. Through figures like these, the Stampede helped instill the mythic image of the West at an early age, ensuring that the romanticization and idealization of cowboy culture could reach audiences of all ages.

The Calgary Stampede’s influence extends far beyond the rodeo arena, shaping and sustaining a powerful cultural mythology that spans media, music, visual art, and celebrity. Through its deep entanglement with popular Western imagery—from mid-century television shows to modern film and comics—the Stampede has continually refreshed the cowboy archetype for new audiences. Musicians like Wilf Carter, youth performers, parade icons, and pop-culture figures have all contributed to a vibrant cultural ecosystem in which the cowboy remains a symbol of courage, independence, and idealized masculinity. Meanwhile, the Stampede’s posters, sculptures, and trophies have visually immortalized this myth, casting the frontier spirit in forms that endure long after each annual celebration ends. Together, these artistic expressions reveal the Stampede as both a product and a producer of Western mythology—a living institution that not only preserves the romantic image of the cowboy but actively reimagines and broadcasts it across generations.