Cowboy Roleplaying

The Calgary Stampede was founded around the idea of preserving and celebrating cowboy culture. Yet, from its earliest days, the event was defined not by working cowboys, but by the enthusiasm of city dwellers who had little direct experience with ranching life. For many urban Calgarians, then as now, the Stampede offered a chance to temporarily step into an imagined past: to roleplay as though they were living in the frontier days of the Old West.

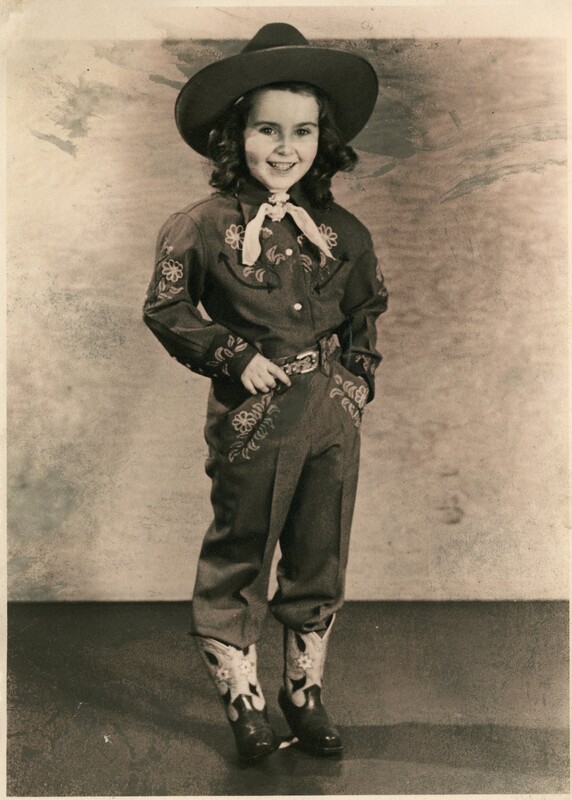

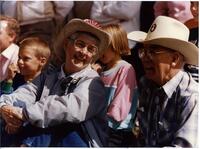

This sense of performance took many forms, from small gestures to elaborate displays of western identity. The most common was dressing up. During Stampede week, office workers, shopkeepers, and families donned jeans, ten-gallon hats, neckerchiefs, and high-heeled boots. A 1955 Stampede program encouraged Calgarians to “dress the part,” describing the festival as “the week when all Calgarians go western and emulate the pioneers who did much to make Calgary and Alberta what it is today.” It urged participants to adopt the “familiar cry” of “Howdy, stranger!”—a ritualized greeting that symbolically collapsed the distance between past and present, between the working cowboy and the modern urbanite.

The Stampede’s transformation extended beyond personal costume. Downtown Calgary became a stage set: businesses decorated their windows with wagon wheels, saddles, and lassos, while storefronts adopted rustic façades meant to evoke the frontier town. In this way, the entire city participated in a form of collective make-believe, transforming itself each July into a mythic western settlement.

The most immersive forms of roleplay, however, took place on the Stampede grounds themselves. Visitors could engage in simulated ranch-life activities—learning how to milk a cow, practicing roping, or participating in line dancing lessons—before sampling “cowboy foods” such as beans, beef, and cornbread. They could then watch professional rodeo events, witnessing real cowboys risk injury or death, before returning home feeling as though they had experienced a small piece of ranch life. The Stampede thus blurred the line between spectator and participant, allowing visitors to enact a sanitized version of frontier labour and to momentarily identify with the cowboy as a heroic national figure.

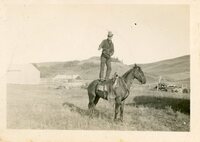

For those who found the brief immersion of Stampede week insufficient, there was always the option of the dude ranch vacation. Dude ranching also known as guest ranching, emerged in the late nineteenth century in the American West and later took root in Canada. Although its popularity peaked in the 1920s, dude ranching remained a persistent leisure practice throughout the twentieth century. These ranches offered urban tourists an opportunity to experience “authentic” western activities such as trail riding, cattle drives, and campfire storytelling in picturesque mountain or prairie settings. Guests stayed for several days or weeks, eating communal meals, sleeping in rustic cabins, and partaking in supervised ranch work, all for a single fee. The emphasis was on immersion and authenticity: guests were encouraged to feel as though they were part of a functioning ranch rather than mere tourists at a resort.

One of Alberta’s most famous dude ranches, the Black Cat Ranch, was founded in 1935 by Major Fred Brewster, a member of Banff’s well-known Brewster family. Located near Jasper, it offered visitors a wide range of frontier-style experiences—horseback riding, hunting, hiking, and evenings spent around the campfire listening to tales of the Old West. In many ways, the dude ranch represented the apex of cowboy romanticism. Tourists willingly paid to spend their vacation performing the difficult labour that real ranchers once endured out of economic necessity. The appeal lay in the fantasy: the chance to step outside modern life and reconnect with a mythologized “better” or “simpler” past.

Both the Calgary Stampede and the dude ranch phenomenon reinforced the cowboy as a central figure of western mythology—a symbol of rugged individualism, masculinity, and moral integrity. Participating in cowboy roleplay, whether for a weekend or a week, became a form of cultural worship: a way of reaffirming the values and ideals associated with settler colonial identity. The cowboy was not just a worker or historical figure; he was a folk hero, a masculine ideal, and a symbol of regional pride. By embodying him, even temporarily, participants in the Stampede and dude ranching performed a kind of nostalgic nationalism, celebrating not only the past but the myths that continue to shape Alberta’s identity today.